“After all, the first light bulbs were less practical than candles.”

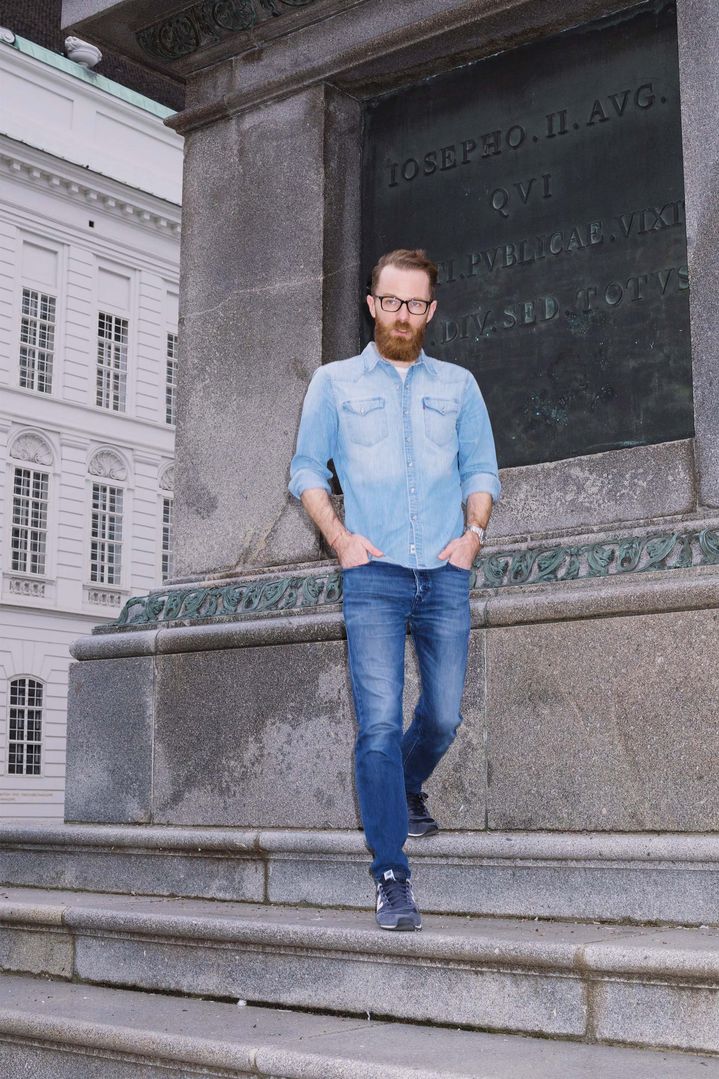

Mr. Cronin, you’re very much at home in the start-up scene. What do you find so exciting about this kind of work?

The fact that it’s about “just going for it.” Diving straight in to testing a vision in practice, before overthinking the practical concerns puts a pin in them. When I was doing my business studies and specializing in advertising and market research, I was taught to do things the other way around. The bottom line was that even with a 90-percent probability, you really didn’t know anything at all. Later, working with start-ups, I learned a new approach: With hardly any hard facts to go on, you make an assumption and test it as quickly as possible, trusting the process to reveal all the important ins and outs. As a result, start-ups are in a permanent state of crisis. They live and breathe chronic uncertainty.

And that’s fun?

With the right team at your side, absolutely! That’s why, by their very nature, start-ups are driven not only by a powerful sense of purpose, but also by people who believe in something enough to want to make it a reality. And that’s in spite of poor pay at first, long hours and the high risk. The key here is defining clear-cut responsibilities. Because hierarchies in start-ups are very flat, areas of work are clearly delineated. If I’m responsible for the website and it isn’t up and running, then I know I had better knuckle down. Simple as that. The fact that everyone is shouldering a bigger responsibility feeds this culture of persevering and getting things done. Which is something I consider absolutely critical. You only really stick at it when you believe in what you’re doing. Of course, that’s true of culture and purpose in businesses across the board—not just start-ups.

So does it make sense for big corporates to take a leaf out of start-ups’ books in this regard?

Yes, you can apply lots of start-up principles to big corporations, above all by pursuing purpose-driven hiring. Indiscriminately adopting start-up trends, however, is not a good idea. There’s a lot of that going around right now—for instance, with the construction of coworking spaces. Always ask yourself why before jumping on the bandwagon. Why do we have coworking spaces? Because we are high-risk companies that could shut up shop at any moment.

What’s your attitude toward perfection?

I like to say that perfection is a moving target. While you’ll never truly achieve perfection, the best way to get as close as possible to it is a never-ending loop of doing, learning and improving. That’s basically the ultimate start-up mantra: Build, measure, learn. Many in my industry would subscribe to the credo that, “If after a year you’re not embarrassed by your start-up, you launched too late.” Of course, that takes a lot of effort. I remember when I was still studying before I stumbled into the world of start-ups, I also had a million ideas. But I never talked about them because I hadn’t yet honed them to perfection. The result of being so tight-lipped was that I also never followed through on them. When it comes to innovation, we need to constantly remind ourselves that you can’t always judge a product or idea at face value. Instead, you have to imagine what they could be and what opportunities they might unlock. After all, the first cars weren’t perfect, either.

Is it only possible to innovate by taking a risk?

The reality is that innovation entails breaking new ground and learning. Much like riding a bike, it usually takes a few scrapes before you get the hang of it. You have to take a risk, although it is, of course, a calculated one. In other words, if I’m teaching my kid to ride a bike, I won’t take him out to the edge of a cliff with no helmet and his tires on fire. By the same token, he won’t learn to ride if you never let go of the back of the saddle. When aiming to innovate, you have to try and anticipate mistakes and setbacks. Just as with a kid and their first bike, chewing them out is not helpful. Otherwise, everyone will lose interest, freeze up and you can forget about innovation.

“

Entrepreneurship should be as accessible as skiing in Austria.”

You want to see this mindset given greater currency. That’s why you’re campaigning at home in Austria for greater social mobility, among other things. Can you tell us more about that?

A few years ago, I had the privilege of co-founding the AustrianStartups non-profit. Our goal is to make entrepreneurship in Austria as accessible as skiing. That comparison might surprise you. At Austrian schools, whoever wants to try can learn to ski without any financial hurdles. Now, we need to do the same thing with entrepreneurship. Sadly, statistics show it’s very often kids from more affluent backgrounds who get the opportunities here. But we also want to reach out to those who are less privileged because we’re sure to find a lot of really smart people who are great at thinking outside the box. In Silicon Valley, they’re referred to as troublemakers. Of course, we don’t expect each of them to found a start-up. Instead, we aim to equip young people from an early age with the tools to improve their immediate environment. By teaching them not only to recognize a solution and the steps to achieving it, but also who to talk to about it. The goal might be to renovate a football team’s clubhouse that burnt down. You don’t need a business degree to do that. It’s easy to teach and can provide tremendous social mobility. What that boils down to is that everyone has equal opportunities to find meaningful work and make a constructive contribution to society.

In broad terms, how have innovation processes evolved in recent years? Have companies and our society become more open to innovation?

While this is nothing new, it’s important to understand that there are two types of innovation. One is incremental innovation. As, for instance, with this glass. It’s great, but you could naturally make it five percent lighter. And then we could maybe go on to reduce the production cost by seven percent. So gradually, the product is improved. In contrast, radical innovation comes into play when we ask: Do we actually still need that glass at all? What for? The automotive industry offers a great example. At first, cars looked more or less like carriages, just with an engine instead of a horse. For decades after their invention, that’s how people made cars. Nobody bothered to ask themselves why cars were so tall. Because that’s the way they had always been. Until at some point people realized that the elevated position was primarily to let passengers see over the horse’s hindquarters. Today, we think that’s pretty funny. But we’re still making the same kind of errors in reasoning.

While it’s true that many companies are slow off the mark when it comes to responding to changing circumstances, start-ups in turn are often accused of celebrating short-sighted quick fixes and promoting a culture of failure. Do you believe that a radical approach to business is sustainable?

Radicalism and radical innovation are, in fact, inherently sustainable. Only businesses that innovate will survive. While incremental change is a short-term solution, radical change works long-term. Ideally, you should cultivate both in tandem. This is known as ambidextrous organizational design. A parent company keeps on pursuing incremental innovation, while a small subsidiary—possibly a start-up—is dedicated to the radical variety. The parent company is responsible for keeping the business in the black next year and in two years’ time, while the subsidiary is charged with ensuring the business will still be around in 10 or 15 years’ time. Will the family business develop sufficiently over the next 20 years for the next generation to take up the reins? Achieving that kind of sustainability requires radical innovation. With this approach, however, efficiency will have to take a back seat. Rather, it’s about the freedom to reinvent the business as a whole. After all, the first light bulbs were less practical than candles because the necessary infrastructure was not yet mature. But whenever I see a light bulb today, I remember how important a culture of perseverance is. By the way, that’s my personal counterpoint to the misleading “culture of failure” stereotype.

What would you post under the Audi hashtag #FutureIsAnAttitude?

I’d like to quote my AustrianStartups colleague and co-editor of our Future Weekly podcast, Markus Raunig: “You have to be smart enough to come up with ideas—and dumb enough to implement them.”